Last Friday, Han, Mike and I attended a GW4 event in Cardiff, where the main topics on the agenda were students as collaborators, and shared projects that we can embark on together.

The day started with brief updates from each team:

Cardiff…

- Have a new space for learning and teaching experimentation

- Are working on a Curriculum Design Toolkit, as part of which they are looking at unbundling content to work in different ways for different markets

- Have a Learning Hub Showcase (http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/learning-hub)

- Have funding that students can bid for, for teaching projects

- Ran a Summer Intern Project – one of which focused on advice in how to use lecture capture

- Had a blank course rollover with a new minimum standard

Bath…

- Have a major curriculum design project upcoming

- Are moving towards programme-level assessment rather than modular

- Have new funding for staff and students to work together

- Are championing a flipped learning approach

- Have a placement student

- Are working on a ‘Litebox project’ (http://blogs.bath.ac.uk/litebox/) where students create an environment where the whole University can learn about new and existing technologies for use in learning and teaching, and share their experiences of them

- Are expanding their distance learning postgraduate numbers

During the second part of the day, we talked about students as producers. Splitting into small groups, we shared our experiences, challenges and tips for working with students on both accredited and unaccredited courses. It was widely accepted by the group that collaboration with students is mutually beneficial. Students are able to move from being passive consumers of knowledge to genuine partners in their education, and we as professionals have a lot to gain from the expertise, connections with other students, and knowledge of life at the university that students can offer us.

The experience of working with students a Bristol, Bath and Cardiff has been positive but limited. All three universities have hired student interns in the past, but would like to do more in terms of making ‘students as producers’ a key underpinning concept in accredited courses. The expectations of ‘what university learning will be like’ puts a dent in the willingness of students to engage with accredited collaborative projects. We discussed how students may see universities as institutions of teaching rather than of learning, particularly as tuition fees have risen, and expect more teacher-to-student time for their money. Our group talked about introducing the idea of innovative learning techniques earlier in students’ degree programmes, and even on pre-university open days, in order to change the expectations of students from traditional lecture-based learning to problem-based modules and more.

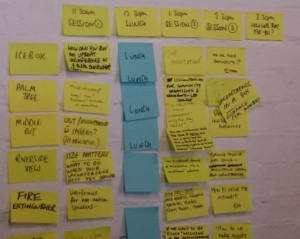

For the last part of the day, we talked about projects that the GW4 could collaborate on, and contributed to this padlet board. We all shared ideas, then each of us cast three votes for the projects we’d like to see most. A common theme was the sharing of knowledge and expertise in areas like FutureLearn, ePortfolios and case studies. We also talked about working together to put pressure on companies or to bid for shared funding in order to improve practice in ways that wouldn’t be possible for a single institution.

Bath have volunteered to host the next meeting in February or March, in which we’ll talk about ePortfolios and assessment.